Fast Fashion: A No-Regrets Breakup

photo credit: @project_stopshop

Maybe, like me, you recycle, opt for a reusable water bottle, and remember your canvas grocery bag on most shopping trips. You genuinely care about the health of the planet and the well-being of others, but you haven’t looked at your clothes through either of those lenses. If this sounds familiar, a quick peek into your closet might offer a frightening reality check similar to mine. I hope you’ll take that look.

In 2014, we (shoppers of the Western world) bought 60% more clothing than we did in 2000 and we kept each garment for half as long. Clothing is the fastest growing element of American landfills and the amount we’ve dumped has doubled in the last ten years. Our closets are stuffed with items that we don’t love, that don't fit, that are poorly constructed, and that are only worn a few times before being tossed or donated. The world is feeling the weight of thousands of overflowing bargain racks full of cheaply made garments. The insatiable desire for clothing at the lowest possible price has created a monster of epic human, societal, and environmental proportions. We don’t have to see the monster or understand what feeds it because most of the production and disposal of our throwaway attire has been outsourced to other countries.

TL;DR:

60% of all clothing produced ends up being incinerated or sent to a landfill within 1 year.

Our collective consumption of low-cost, low-quality apparel has more than quadrupled in the last thirty years and this glorified focus on bargain hunting at the expense of all else is not only decimating the planet, but also exploiting its most vulnerable women in the process.

Most of our apparel is now made from cheap synthetic fibers such as polyester (plastic), which are produced from fossil fuels and take hundreds of years to decompose, creating enormous waste and contributing to global warming.

Average Americans buy around 70 pieces of apparel each year and only regularly wear about 18% of what they have in their closet. (guilty!)

Apparel production is a dirty business, requiring an incredible amount of natural resources and the process results in the runoff of pesticides and chemicals into water supplies around the world, polluting the earth and causing human health problems.

Our well-meaning donations are drowning foreign countries in our trash to the point that many are actively rejecting our castoffs.

Our current rate of consumption and disposal is unsustainable but is expected to grow exponentially as the global population and consumption rates increase.

The industry needs an overhaul and fortunately, brilliant minds are at work and there are many easy (and free) steps you can take to minimize your impact.

Diving into this subject can be a bit overwhelming, so I created a helpful ethical fashion crash course that outlines the most impactful books, documentaries, podcasts, and inspo to guide your journey.

Quick nav:

my why | sobering stats | what is fast fashion

shopping discount | shopping designer

history | influencers | consumerism

feminist concerns | environmental concerns

donations | what you can do | looking forward

“Cheap is a strategy, a practice, a violence that mobilizes all kinds of work - human and animal, botanical and geological - with as little compensation as possible.”

but don't you work in fashion?

Indeed, I do. I’ve spent the last five years as a personal stylist and in that time, I’ve styled more than 11,000 women around the U.S. - this means that 60,000 pieces of apparel, shoes, and accessories have passed through my hands. For the last three years, I’ve been immersed in the luxury brand universe for clients where the minimum spend on a blouse is around $250 and this gave me a chance to look more closely at the relationship between cost and quality. My direct contribution to this outrageous consumption cycle has induced a considerable amount of guilt and by the end of the article, you’ll know why. The side gig I picked up to pay off my student loans dramatically changed how I view the fashion industry and, more than any other factor, inspired my transition to conscious consumerism.

Writing in this area can quickly become preachy (read: nauseating) so, I’m offering a condescension-free personal history and noting that it took me years to get to a place of, “Ok, I’m serious and I’m going to action this knowledge now.” Maybe I can convince you to move more quickly than I did? I hope so.

That said, I had a fairly standard small town 90’s childhood (original VSCO girls, I see you, and I hope you kept those scrunchies.) Having choices in the fashion realm was a luxury that rural life didn’t afford and it wasn’t until I landed a high school job cleaning hotel rooms that I could begin to pay attention to trends and think about what I wanted to wear or how to express myself through fashion. Back then, going to the mall was a special treat (and a 45 minute drive.)

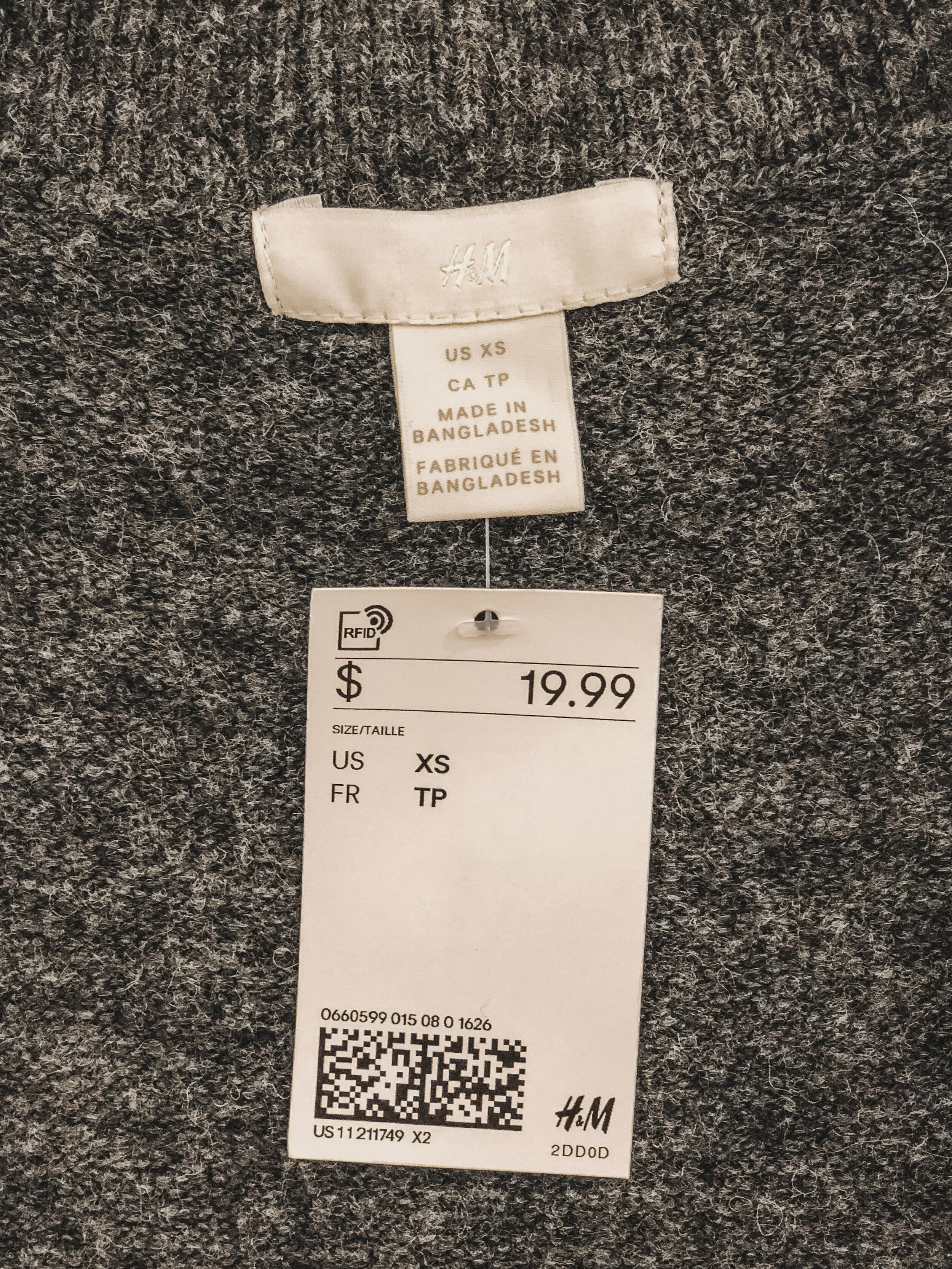

The rise of fast fashion giants like H&M and Forever 21 perfectly aligned with my undergraduate years, where I studied biology, worked two jobs, and figured out how to put together a killer night-out ensemble on a minimum wage budget. Making up for lost time after grad school, I treated myself to designer bags, jeans, and shoes using the logic that I had earned it and thinking that higher-end brands meant better quality. I wasn’t wasting money on brand marketing, I was investing. I never once thought about who made my clothing, how long it would last, or what impact my shopping approach was having on the planet when multiplied by millions of people.

Well-meaning friends have encouraged me to start a fashion blog for years and most assume that my years as a stylist mean that my closet is filled to capacity with Insta-inspo and trendy pieces snagged with an employee discount. While that was partially true at the onset and the remnants of a life with different goals are still peering out of my closet, the unexpected twist was that styling thousands of clients each year actually made me reevaluate everything about the industry I happily embraced with little critical thought for most of my life. Today, the absolute last thing I want to do is become another source of consumerist inspiration, so unless I’m inspiring you to be a more conscious shopper, any other use of the term “influencer” makes me cringe.

Most of my twenties were a decade of stark contrast, and I completely embraced the #closetgoals, flat lays, and savvy marketing ploys that generate enormous profits in the $3 trillion industry that manages to convince most of us that cheaper is better and more is definitely better. There was no stopping to consider the fact that a human being made the shirt didn’t quite fit, but I bought anyway because sales! There were no thoughts about how depressingly short the lifespan of my H&M mini skirt would be (or where it would end up at the end of its life), and there was zero comprehension that every piece of polyester filling up my closest was the equivalent of wearing an unrecylable plastic bag destined to spend its last days in a landfill heap polluting the earth and water around it. I honestly had no idea how to evaluate the quality of a garment even if I wanted to.

“Regardless of what your background is, we can all agree on some really basic things—no one should die to make a t-shirt, and we shouldn’t be pouring toxins into our planet.”

the wake-up

Like every breakup a woman knows needs to happen, I can trace the beginning of the end back to a few still-memorable moments where I started to question things. (True to form as far as breakups go, the actual end happened far too long after the moment I knew it needed to happen and I can look back with perfect clarity on moments I failed myself with inaction.) The end should have been the moment of nagging guilt when I saw unworn tops hanging in my closet months after I bought them, still-attached tags reminding me that I didn’t really need more sweaters. Or the day at Goodwill where I realized that most of what I had just donated was only worn a few times. Or the afternoon I noticed the stitching fraying on a new Louis Vuitton bag and felt ridiculous for buying it and assuming higher cost meant higher quality. Or the evening I read that 60% of all clothing produced ends up in a landfill or being incinerated within one year. Or the moment my heart sank as I learned that women make up nearly 80% of the garment workforce and many, particularly in fast fashion production, are underpaid, abused, and trapped in a cycle of perpetual poverty… all so that I can buy a t-shirt I don’t need for less than I pay for a latte. After far too long, it finally dawned on me that it’s impossible to call yourself a feminist or an environmentalist while supporting an industry that is destroying the planet and exploiting women (and children and prison labor) to do it.

cringe worthy stats

Attempt even a quick foray into the world of ethical fashion and you’ll find yourself face-to-face with some horribly depressing statistics. While claims that the fashion industry is the “second most polluting industry in the world” abound, technically, it’s not (quite) and in a world of “alternative facts” spun to fit a narrative, the researcher in me insists that I carefully articulate just the facts, which don’t need embellishment for impact anyway:

60% of all clothing produced ends up being incinerated or sent to a landfill within one year.

85% of our old clothing ends up in a landfill. 25 billion tons of textile waste are generated every year.

Worldwide clothing production doubled from 2000 - 2014. Most of that gain was in fast fashion.

The number of garments purchased each year by each consumer increased 60% in that same time period and now hovers around 70 pieces/person/year.

80% of garment workers are women and only 2% receive a living wage. The apparel industry also exploits child and prison labor to keep costs low.

Americans buy 5x more clothes today than in 1980. In that time, a $500B primarily domestic industry has grown to a behemoth $2.4T global industry and we’ve lost sight of what happens in the supply chain in the process.

As we outsourced apparel jobs in favor of cheap labor, the U.S. textile industry lost 1.2 million jobs (75% of the labor force) from 1990-2012, creating factory ghost towns along the east coast.

Clothing is the fastest-growing element of American landfills and the amount we dump has doubled in the last 10 years.

Between 700,000 and 6,000,000 microfibers are released when washing an average load of synthetic fabrics (polyester, nylon, acrylic.) The fibers are too small to be filtered out and end up in our waterways and oceans where they’re consumed up the food chain until we, too, ingest them.

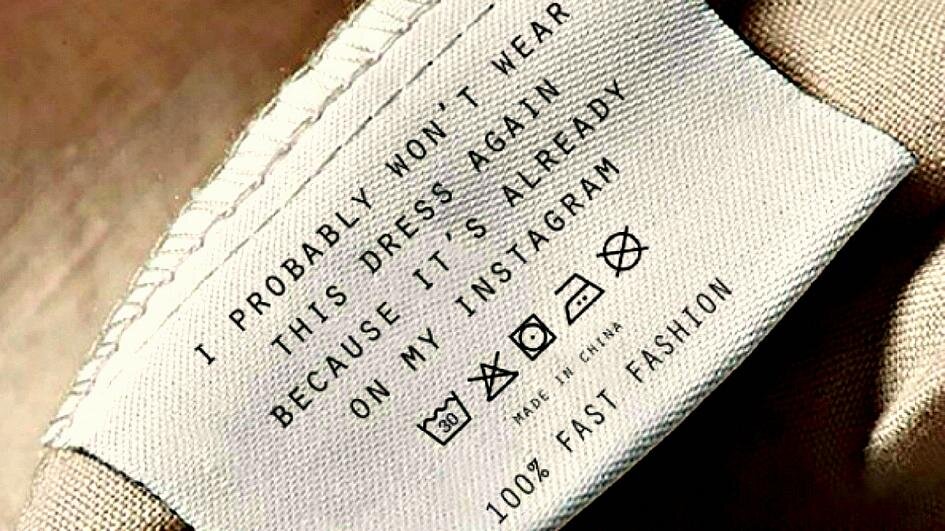

A summer 2019 survey revealed that Brits alone would spend $3 billion on single-use fashion items for one-time events like vacations, Glastonbury, and Coachella. 25% admitted they’d be embarrassed to be seen wearing an outfit more than once.

713 gallons of water are needed to grow (conventionally) enough cotton to make a single t-shirt. This is 3 years’ worth of drinking water for one person.

Around 10% of global carbon emissions are produced by the apparel and footwear industries. This number is expected to rise steadily as emerging economies increase consumption to match the rest of the world.

20% of freshwater pollution comes from textile treatment and dyeing and 25% of all chemicals produced worldwide are used in the apparel industry.

The apparel industry’s production impacts on climate change increased 35% between 2005 and 2016 and are projected to steadily rise in 2020 and 2030.

35% - 50% of all online clothing purchases are returned (often for fit.) The free shipping/free returns model is turning out to be an environmental disaster because often, the items go straight to a landfill because they’re not considered “first-tier” and resellable.

Americans attempt to recycle or donate only about 15% of their old clothing and about 80% of what is donated ends up in a landfill anyway. (Partially because we’re as bad at donating as we are at recycling and partially because the quality of what we donate has plummeted in the last few decades.)

so what *is* fast fashion?

It’s helpful to think about what fast fashion is designed to be - disposable fashion. Fast fashion companies produce a high volume of cheap clothing that isn’t meant to last. It’s designed to be on-trend and cheap enough that you don’t need to think very hard about buying it or tossing it (aka the purchase impulse threshold.) Picture the designer copycats - stores where you see new pieces on a weekly basis, traffic is solicited through alluring sales, and profits depend on moving a high volume of inventory with a smaller profit margin on each piece. We’re talking about the well-known offenders like H&M, Forever 21, and Zara, but also Old Navy, Target, Wal-Mart, GAP, Urban Outiftters, Express, Charlotte Russe, Victoria’s Secret, Nasty Gal, and Abercrombie + Fitch (list not even close to all-inclusive.) A designer can spend a year of creative energy developing a collection only to have it ripped off by a fast fashion company that can have a similar-looking dress on shelves in 6 weeks - a process that devalues art, design, and the labor associated with the art form that fashion is intended to be.

Anyone who has shopped at SheIn/Romwe/ChicWish (the almost indistinguishable direct-from-China business models) knows that when you pay $6 for a dress, you get a dress that looks like it should cost $6 - the patterns don’t line up, the stitching isn’t straight, the thread colors are odd, the sizing is off, the print is only on one side - and sure, it might look cute for a photo, but you’re only going to wear it once or twice. Amazon Prime is to 2019 what Forever 21 was to 2004 (and part of the reason F21 filed for bankruptcy), peddling the same poor quality fast fashion with the exception that in 2019, the pieces are in our mailbox in 6 hours. There are thousands of bloggers ready to recommend a $12 sweater or $10 “swimmy” that you can blink onto your doorstep thanks to Jeff Bezos. The same factories are producing all of this landfill fodder.

what about department stores?

While the quality may not seem as blatantly terrible, much of what is sold in most department stores like Macy’s, Kohl’s, and JCPenney isn’t functionally different than fast fashion because these retailers adapted their business models to compete with the tremendous success of the flavor-a-day brands. (It’s also because, as consumers, we don’t demand quality - we demand sales, so there’s little financial incentive to create a higher quality product.) Identifying fast fashion is less about Scarlet-Lettering a retailer as fast fashion (bad) or not fast fashion (good) and more about learning how to evaluate what you’re buying - being able to compare fabrication, construction quality, business practices, and being able to recognize greenwashing as the deceptive facade that it is.

or discount stores?

Closeout stores like TJMaxx, Marshalls, Ross, Saks Off Fifth, and Nordstrom Rack are either selling leftover merchandise from the originally problematic retailers or they’re having low quality merchandise intentionally produced for them, fully aware that they’re sacrificing quality so they can sell the clothes as markdowns. The “Maxxinista” is a myth. Outlet stores are also known for producing lower-quality pieces designed specifically for outlet sale - J. Crew, Banana Republic, GAP, Coach, and Kate Spade are well-known offenders. No, you’re not getting a better deal; you’re getting a lower quality handbag and cardigan. This year, a class-action lawsuit settled against Banana Republic required them to pay $114-228 million for pretending their outlet items were the same as their traditional inventory and for using misleading price references to trick you into thinking you scored a great deal.

... or high-end designers?

If you’re thinking you’re safe because you’re buying high-end, you’re not alone. The automatic association of cost with quality is a tough mental barrier to break through. Yes, there is a difference in the fabrication and construction quality between what you’ll find in Target and what you’ll pick up in Saks, but I’ve seen firsthand that paying twenty times more for a dress doesn’t necessarily result in an equivalent increase in quality. It definitely doesn’t mean that your dress was manufactured with any more concern for the environment or the woman creating it.

I was initially surprised when I heard an industry expert say, “There are about two brands where the quality warrants the cost and for every other luxury item on the market, you’re paying for their brand image.” After five years as a stylist, I couldn’t possibly agree more and have become far more selective when adding pieces to my closet. I’m going to pick on Revolve because even though I tend to love the aesthetic, I’ve been consistently disappointed in the quality at higher price points. A $300 dress is likely to be a mashup of mixed synthetic fibers. For the most part, the construction is better, but honestly, not that much better and synthetic fabric is still synthetic. Unlined dresses are still unlined. Cheap zippers are still a nightmare whether you paid $25 or $300. Price point and brand name guarantee nothing.

Can you make the argument that a great designer handbag will be carried for years, and thus, it’s worth the cost and better for the world than purchasing a less expensive one every few years? Sure. I’d like to justify my love of Chloe and Celine, but I’ve tried and I can’t. Instead, I’d argue that you could take the $2,000+ you’re going to drop on a Louis and support a company where the supply chain is transparent, where materials are ethically-sourced, where employees receive a living wage with health benefits, and where safe working conditions are monitored and reported all while still carrying that bag for years.

Most high-end designers are incredibly sketchy (Stella McCartney and Eileen Fisher excluded) when it comes to supply chain transparency, working conditions in their factories, and most fail to even mention any sort of sustainability practices. Several luxury brands, like Burberry, were skewered in the press for burning unsold inventory rather than “diluting their brand value” by selling it at a lower price. Sadly, if you destroy your unsold inventory under the supervision of U.S. Customs, you’ll even get a refund of the sizable import fees. Some countries even allow you to use your incinerated loss as a tax write-off, so there’s more than one reason to send your boujee stock up in smoke. Should we accept that the most profitable and highly-esteemed companies with the greatest capacity to make positive change are putting the least effort into doing so?

how'd we get here?

Understanding how we’ve arrived at this place of excess can help us give ourselves (and each other) a break while empowering everyone to make better choices, see reality for what it is, and resist the marketing pressures we’re bombarded with every day.

Throwaway threads weren’t always a thing. In the 1930’s, a woman could expect to have about 9 dresses in her closet, tailored to her, carefully maintained, and worn for decades. As recently as the 1960's, 95% of clothing purchased by Americans was made… in America. At that time, Americans spent about 10% of their annual income on clothing and shoes, or about $4,000 per year in today’s dollars. Fast forward a few decades and only 2-3% of our clothing is made in the U.S.A. Today, the average American spends less than 3.5% of her budget on clothing and shoes. Yet, somehow… we buy a record amount of clothing each year - around 70 pieces per person. We only regularly wear 18-20% of what we own, most of it doesn’t spark any Marie Kondo joy, and eventually off it goes … either into a donation cycle (discussed later) or more directly into the trash. Fashion has transitioned from utilitarian to performance art.

Consumer demand for cheaper and cheaper clothing (and yes, corporate profit aspirations) incentivized companies to pursue cheap overseas labor markets in a fierce competition to see who could offer the lowest price on your tee. From 1990 - 2012, the U.S. apparel industry lost 75% of its labor force - 1.2 million jobs - as Americans were replaced by lower-cost workers in Latin America and Asia. Abandoned and repurposed factories along the east coast tell a story of job loss far greater than the coal industry losses dominating our news cycle. As it turns out, you can't simultaneously insist on buying $5 t-shirts and truly support American jobs because most Americans aren’t lining up to take a $2/hr. job with no medical benefits that includes mandatory unpaid overtime in a factory that’s falling apart and a manager who’s physically abusing them. To make that $5 t-shirt, someone somewhere has to be willing to work for a pittance while facing the inevitable safety and environmental consequences that come with cutting corners to save money. This article is encouragement to consider those people - those you don’t see in places you don’t live (or those right here in LA.) Tell me how anyone can live in LA on $6 an hour.

influencer culture feeds consumption

The popularity of YouTube clothing haul videos and Instagram “influencers” with daily stories full of "must haves" suggest that I wasn’t alone in my embrace of consumerism and the ideas that our main shopping goals should be to see 1. how much we can buy and 2. how little we can spend. I’ve noticed that outfit compliments generate an obligatory disclosure of purchase origin and a humble brag about whatever steal was scored at purchase - some version of, "Wow, I love your top!" is followed closely by, "Thanks! Can you believe I got this at Target? $7!" Deal-finding is an Olympic sport in American culture.

In this camera-ready age, being appropriately on-trend means keeping up with weekly trends designed to generate profit by turning a previously seasonal hunt for new clothing into a weekly (or daily) adventure. Social media creates a system where everyone feels pressure to dress in preparation to be photographed (an approach previously reserved for celebrities), buying into the idea that you can’t possibly re-wear something you have been previously photographed in. Unfortunately, our brains are wired to enjoy entire the process tremendously.

Everything is shoppable now - Pinterest, Instagram, Facebook - one click and into a cart it goes and soon after, you get an email reminding you that you have unpurchased items in your cart. Tech giants have all of our data, so in 2019, Instagram knows I’m going to want an ethical bra before I do. I’m on mailing lists for a dozen fashion retailers ranging from smaller boutiques to larger international brands and I get a daily email with new inventory from every single one of them.

The realities of fast fashion aren’t obvious when you’re thumbing through those conveniently shoppable posts full of puppies-as-props and adorable babies (also clad in shoppable attire.) I follow a few bloggers who proudly display their front porches filled with packages each day and who have enough clothing to post a new outfit every few hours - every. single. day. What used to pique my interest now makes me nauseous and not just because every blog post has a disposable Starbucks cup in it. The woman pictured above is beautiful, has an impeccable sense of style, and worked hard to grow her following to over a million people. If only she used that influence to inspire people to buy something other than fast fashion, $6,000 handbags, and disposable Starbucks cups…

A crowning achievement in BloggerLand is being accepted into content monetization platforms (commission-generation companies) like rewardStyle, where honest bloggers will tell you about the pressure they face to rep whatever clothes are part of their particular ecosystem and its retail partners/affiliates. (This is one reason why you see bloggers wearing the same thing all the time.) Most ethical companies, which are often much smaller and have less capital, can’t afford the fees charged to enter and remain part of the ecosystem, so #ootd is often a sea of retail giant sameness.

A panel of sustainability advocates, including bloggers reevaluating the consumption system and how they participate in it, will be speaking at Good Together Live in a few weeks and I’m really curious to hear their thoughts. I know there is an overlooked and ever-increasing population of women like me having an existential crisis after confronting some inconvenient truths about the fashion industry.

“Next time your favorite fashion blogger says she, “love love LOVES” a $3,000 Celine purse, as yourself … does she really love it? Or does she love the $300 she’ll earn when you buy it?”

consumer culture surrounds us

Influencers thrive in an American culture defined by the unapologetic pursuit of individual happiness (impact on others or the planet? - shrug emoji) and the message reverberating from every corner of society is, "buying this is the secret to happiness! And also this. And this." The more money we make, the more we spend - nicer clothes, a nicer car, a bigger house. No episode of House Hunters would be complete without some assessment of closet size and no one questions the need for space to store 300 shirts and 150 pairs of shoes. If we can’t do cartwheels in our closet, walls will need to be removed so that we can fashion “adequate storage space” immediately.

We know that buying more won’t make us happy, but that doesn’t stop us from trying, nor does it inoculate us against the subtle influence of increasingly sophisticated marketing ploys. We joke about our right to “retail therapy” after a hard week, aware of the tiny high we get from purchasing something new and equally cognizant of how short-lived that mood boost will be. Women, in particular, are laser-targeted with marketing that preys on our insecurities. We’re indoctrinated from childhood with the perspective that success and respect require the devotion of considerable mental energy to the pursuit of an “ideal" standard, generally (and unfortunately) understood as thin, white, affluent, and surrounded by stuff.

I’ve always been fascinated by the complexity of behavioral economics and America’s consumerist culture certainly makes an interesting case study. Questions related to how social media influences consumption, how consumer culture impacts mental health, how filling social voids with physical things leads to emptiness, and why we’re simultaneously more and less connected to each other are answered in a few of my favorite books. Try Thinking Fast and Slow or The Undoing Project if this topic sounds interesting. Comedic rambling aside, Recovery by Russel Brand is also one of my favorites. In it, he tells his story of becoming famous and constantly chasing the next high brought by each new level of wealth - more stuff, more drugs, and more sex. I usually recommend it as a humorous and deeply moving intro to minimalism and conscious living because he’ll have you laughing out loud as you consider the pointlessness of materialism and a never-ending pursuit of “more.” I recommend the audiobook because there’s no substitute for him reading his own book in that British accent.

For now, I’ll summarize this section by saying that we’re products of the culture we live in, so don’t personally internalize the guilt or declare yourself an irredeemable glutton for buying a bunch of cheap clothes and living in the world the way society has taught you to. Being products of this culture doesn’t mean that we need to accept what we’ve inherited or participate in it the way that profit-hungry corporations hope we do, and that’s the point.

the feminist case against fast fashion

Women. owe. each. other. more. This topic deserves far more consideration than a paragraph within an article. A staggering 80% of garment workers are women. Though globalization promised high-quality employment opportunities for disadvantaged communities while delivering low-cost goods to the masses, it only fully delivered the latter. Women in countries like Bangladesh, Vietnam, and Indonesia work in unsafe factories (with notably high rates of abuse and sexual assault) for poverty-level wages. Most are not offered health insurance and can’t afford to buy the clothes they’re making.

Heartbreaking realities are the norm, not the exception. Fashionopolis detailed the tragic story of a factory worker in Sri Lanka who got a toothache and was forced to take out a loan to visit the dentist. When she couldn’t make enough to repay the loan, she had to turn to sex work to pay it off - all while working 12 hour days making t-shirts for Western consumers. Demands for rights are met with violence, attempts to unionize are quashed with threats, and workers are told what to say when interviewed by outside agencies. Tragedies like the Rana Plaza collapse sparked worldwide outrage and consumer backlash that was ultimately short-lived. As recently as 2017, similar situations were reported in LA’s factories, too, so the problem isn’t as far away as we might think - not that distance should matter.

We’re so disconnected from the people producing much of what we buy that it was embarrassingly difficult for me to picture a woman making my clothing. How do you reconcile the fact that another woman is being exploited so that you can pay an unreasonably low price for a piece of clothing you probably don’t even need? How do you reconcile that another woman is working ridiculously long hours but still living in poverty while the profits of her efforts go to a CEO and shareholders because you, as a consumer, haven’t considered the impacts your purchasing decisions in making these companies so profitable? Translated: a (mostly) Western desire for more and cheaper stuff is directly responsible for trapping women in a cycle of abject poverty. How do you reconcile that? The answer for me was: you can’t.

I recommend The True Cost to anyone even mildly curious about these issues. Almost everyone I know doing work in this space cites this documentary as being THE thing that inspired their action. It’s unforgettable. It will make you cry. And think. And (hopefully) act. You can find a complete list of my favorite ethical fashion resources here.

the environmentalist case against fast fashion

Understanding fashion’s environmental impact requires a look at the entire production cycle and considering the full impact of the supply chain is a sobering mental process. The actual cost of a $5 t-shirt* includes the 713 gallons of water needed to grow the cotton, the volume of pesticides sprayed on the cotton field, the river pollution and cancer caused by that spraying, the fossil fuels extracted to produce the shirt’s fibers, the women exploited to sew it, and the environmental impact of its journey to the landfill (where it ended up after less than a year of use, on average.) *And that’s if your t-shirt is cotton. If it’s a synthetic fiber (like polyester), think of the t-shirt as a finely woven plastic bottle that will take hundreds of years to break down after spending its life depositing tiny plastic particles into the environment for us to eat, drink, and breathe.

Apparel production is a dirty business. The UN estimates that the fashion industry consumes more energy than the aviation and shipping industries combined. The Pulse Report expects fashion industry emissions to increase 63% by 2030 as demand from developing economies catches up to the rest of us. Apparel production is water-intensive and fibers are often grown in areas already suffering from water scarcity. The Wrap Report estimates that a single t-shirt and pair of jeans require between 2,700 and 5,300 gallons of water if created from conventional cotton. Attempts to maximize crop yields result in the use of fertilizers and pesticides which pollute water and pose a significant threat to human health. An incredible amount of waste is created at every part of the production cycle.

Graphic credit: Quantis 2017 Metrics of Sustainable Apparel

Though it touches on just one of the apparel industry’s many environmental repercussions, River Blue does a fantastic job of illustrating the impact of apparel industry pollution in both environmental and human terms. The expert interviews are insightful and the second half of the film provides hope. Most importantly, it offers ways to become engaged.

don't donations absolve us?

As well-intentioned as we are, donations don’t address the consumption problem. If you’re like me, you probably picture your bags of donated goods being distributed to those in need in the local community. Unfortunately, that’s not the way most donation centers work anymore. The harsh truth is that we donate far more clothing than anyone actually needs (because we buy far more clothing than anyone actually needs.) Only 20-25% of donated clothing ends up being resold and the rest gets packaged up into giant bundles and shipped to developing countries. The excess donations arriving in places like the Caribbean, Asia, and Africa, saturating the local clothing markets and making it difficult for local businesses to compete. In 2016, the East African Community (Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda) attempted to phase out this import of secondhand clothing that is devastating local businesses, but in 2018, the Trump administration threatened a trade war (citing the loss of 40,000 U.S. jobs) and the EAC backed down. Message sent: your nations are our landfill and there’s nothing you can do about it. A large percentage of our excess clothing ends up in foreign landfills because it’s often too big, too damaged, or too dirty to be resold.

This isn’t to say that you shouldn’t donate and make the most use possible out of what you already own - you absolutely should. There’s a meaningful and effective approach that goes beyond offloading a giant bag of random pieces at Goodwill and I’ll cover that separately.

what can you do?

Fortunately, a LOT. And most of it costs nothing. You might even find that you save money by adjusting your approach (I did!) It’s definitely easy to get overwhelmed with the enormity of the problem, though. For me, the overwhelm resulted a period of not knowing where to start (I literally just refused to buy anything for almost a year) and of questioning how much impact one person’s choices could actually have and why I should bother. The truth is that our individual actions have tremendous power to effect change, particularly as consumers. Money talks and dollar voting works, so we can either spend energy thinking of reasons not to act, or more wisely invest our time doing something about the world’s injustices. (*Enneagram 1 waving energetically*) This is a difference of going along with the masses or trying to live a life (and build a wardrobe) that reflects your values.

Conscious Closet Basics

Choose one to start and expand from there. Know that it takes time to do it right and the goal is always progress, not perfection.

The no-brainer, least expensive, and most rewarding of the list: buy less. Only buy what you love (love not like), what truly fits, and what works with your current wardrobe. Leave the tempting sale pieces on the rack. This is easier if you…

Get organized. All of the following suggestions are easier to implement if you do a closet purge and are left with core pieces you love and can slowly build on. I recommend a closet organization app to everyone I style. It will change you shop, how you dress, and how you pack. If you have too many pieces to enter into the app, you have too many pieces.

Define your style and shop accordingly. I always recommend a neutral palette with a few favorite accent colors. Staying in your scheme makes shopping and mixing pieces easy. My palette is a neutral base (black/cream/grey/navy) with accents of mustard, cognac, and blush.

Consider a minimalist or capsule wardrobe full of high-quality basics and pieces that are easy to mix and match.

Love what you have. Already have a few regrettable pieces? Get as much use as you can out of them. Reconsidering your shopping approach doesn’t mean you have to ditch everything and start fresh. If you see pieces in my posts that aren’t linked, this is why.

Learn how to identify quality and how to recognize superior stitching, fabrication that will stand the test of time, and finishes/embellishments that are made to last. Invest in pieces you’ll treasure - the highest quality items in your price range. If the sticker shock of higher quality items gives you pause, consider cost per wear when you’re purchasing something. The math on a $20 sweater worn twice vs. a $100 sweater worn ten times is the same.

Educate yourself on fabrication basics and choose natural fibers as often as possible. Avoid chemically-produced synthetics (polyester, nylon, acrylic) in favor of natural fibers (organic cotton, hemp, wool, silk, cashmere.)

Be willing to do some homework on the brands you support. Decide what your issues are - workers’ rights? Environmental impact? Both? Research and ask questions. Companies doing it right are happy to provide information. View your dollars spent as votes toward the kind of world you want to live in.

Know your measurements. Write down your shoulder, bust, waist, and hip measurements and your inseam in different pant silhouettes. Lay your favorite dresses flat and collect the same measurements. Use these when shopping online to avoid returns and ensure a great rental and secondhand experience.

Rent instead of buy. Renting isn’t just for weddings anymore - also think vacations, holiday parties, music festivals, Halloween costumes, date nights, or and even the work week. The number of rental options is increasing along with demand and openness to the beauty of style without ownership, so I’ll be writing a separate piece on my experiences comparing rental services.

Buy secondhand. If you live in a thrift store desert like I did before coming to California, fear not. Sites like thredUP, Poshmark, and eBay provide tons of opportunity to efficiently thrift shop. The key is to know what you’re looking for and what your measurements are.

Sell secondhand. I’ve “made” (recouped) thousands of dollars selling my gently-used clothes on eBay (and now a few other sites) since 2003. Extending the life of pieces already in existence by a mere 9 months reduces the carbon and water footprint by 20-30%.

Shop local. Don’t assume local = ethical. Plenty of local boutiques are stocked with the same pieces you can buy on Amazon or SheIn, but many of the places trying to source ethically are smaller, local stores. See #6 to tell the difference.

Extend the life of your current clothing. Wash less, wash cold, avoid the delicate cycle, line dry. Learn to repair minor issues. Find a great tailor. 1/3 of apparel’s carbon footprint comes from the way we care for it.

Donate with intention. Follow the basic rules of donation etiquette and consider how to find the best new home for the pieces no longer in your lineup. Maybe it’s a local thrift store, a women’s shelter, or a local college’s career fair. Ask what each organization needs before donating.

Find new inspo. Listen to podcasts, sign up for newsletters, follow a few Instagram accounts that keep this at the forefront of your mind in a society that’s happy to fill the space with other marketing agendas.

Get involved. Vote for candidates that support living wage legislation, environmental protection legislation, and clean energy. Look for legislation supporting small businesses and sustainability initiatives.

change is coming

..and I don’t say that just because Forever 21 filed for bankruptcy as I was writing this (they were more a victim of consumer conversion to e-commerce than of the abandonment of fast fashion.) Regardless of the issue at hand, “wokeness” of any kind is learned. The journey is ongoing and no one is perfect or has all the answers. Better information is constantly emerging and there’s always more to learn and more to do. We can all make improvements and rather than focusing on shortcomings in ourselves or someone else, striving to do better and encouraging others to do the same is where the small steps of progress become a force.

I believe that fashion can be a mechanism of self expression as well as a force for good - it doesn’t have to be strictly about materialism and vanity. Fashion can be humane and sustainable. We’re seeing this vision come to life in more companies each day but we, the consumers, will drive the speed of that change.

We’re getting closer to a world where we’re prouder of the story behind the creation of our favorite bag than we are of the label. Prouder of the community the purchase supported than we are of its price tag. Prouder of how long it will last than how fast we jumped on a trend. I want to live in a world where the money one woman spends lifts another woman up rather contributing to her exploitation, where the sign that we’ve “made it” isn’t what’s embossed into a handbag. In that world, when someone tells me they like my sweater, I’ll tell them about Fibershed and the incredible work they’re doing here in California. Nothing would make this introvert happier than exchanging superficial pleasantries for meaningful conversations that drive positive change. Maybe someday, #outfitrepeater and #secondhandfirst will outnumber #LTKitunder50 and #LTKsalealert on the ‘gram.

Melania Trump’s tone-deaf wardrobe choice on a 2018 visit to immigrant detention centers drew worldwide criticism for its controversial screenprinted message. Though the rationale (or lack thereof) for this layering selection varies depending on which news outlet you watch, the fact remains that it was a 2016 Zara production that retailed for $39. Zara produced 450,000,000 items that year and its founder is one of the richest people on the planet (net worth $63B) thanks to his ability to convince everyone that buying 70 pieces of apparel per year is normal and necessary. That leaves us all to answer her question.

I really do care. Do you?

Photo credit: Zara, AP - Andrew Harnik

curious about your fashion footprint?

thredUP partnered with independent environmental research firm Green Story Inc. to create a Fashion Footprint Calculator. It’s a tool anyone can use to quickly determine their carbon footprint associated with clothing purchase, care, and disposal habits, and to find out how small actions like shopping secondhand or air drying your clothes can make a big impact in reducing it.

2010

A very regrettable result from my college years.

2020

A massive improvement thanks to small but impactful life changes.

want to learn more?

In what I affectionately call an “ethical fashion crash course,” I included a list of the most impactful books, documentaries, podcasts, and other inspiration that shifted my perspective and taught me an incredible amount.